Ohio State study breaks new ground in eliminating paralysis after aortic aneurysm surgery

A recent study conducted by an interdisciplinary team of investigators at The Ohio State University College of Medicine is gaining national attention for its latest findings identifying the causes of spinal cord injury and paralysis in patients who must undergo surgery to prevent aortic aneurysm rupture, a medical emergency that kills approximately 15,000 people each year in the United States.

The interdisciplinary team of 22 scientists and clinicians published a five-year, preliminary study explaining the differences in the pathophysiology of aortic aneurysm (AA) surgery between open repair (OR) and the less invasive endovascular repair (EVR). The study refutes the long-held belief that the same physiological processes are at play in both types of surgical procedures. The two surgeries inflict distinctly different kinds of damage to the spinal cord, according to Hamdy Elsayed-Awad, MD, an anesthesiologist at the Ohio State College of Medicine and lead investigator in the study.

“This preliminary study demonstrating the differences between OR and EVR pathophysiology indicates that the two processes are drastically different — they are two disparately different diseases and, therefore, we have to treat them as such,” he says. “Any good science always raises more questions than answers; but, in the end, we want our work to offer our patients some hope that we are on the right track to beating this deadly occurrence.”

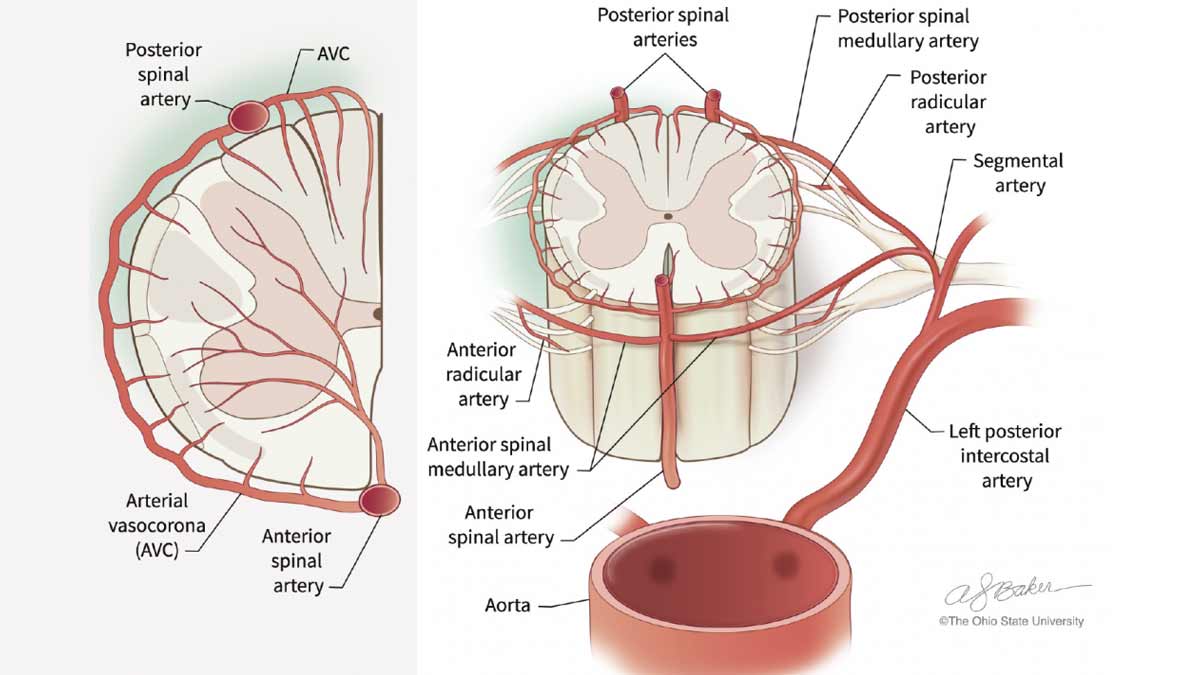

The team has been able to demonstrate just how those physiological differences produce differences in spinal cord damage using animal models. Their work shows how the processes involved in OR can cause damage to the gray matter, or the neurons of the spinal cord, which cannot be replaced or repaired. On the other hand, EVR retains neuronal integrity but inflicts damage on the white matter, or the outer layer of the spinal cord, an area that assists in relaying signals from the spine to the brain.

These physiological changes were assessed using a variety of measurements, including behavioral assessment by a veterinary expert. The assessment revealed unique patterns of proprioceptive ataxia and evolving paraparesis in EVR versus irreversible paraplegia in OR. MRI tests showed posterior signal in lumbar spinal cord (SC) after EVR, compared to central cord edema after OR. Histological analyses confirmed the qualitative differences between SC damage to the gray matter in L3 – L5 after OR, versus white matter edema after EVR caused by EVR, in accordance with results obtained from behavior and MRI analyses. Metabolome analysis demonstrated a distinctive chemical fingerprint of cellular processes in both types of intervention.

The study results provide clear, strong evidence that the mechanisms of SC injury from EVR are drastically different from those that result from OR. This new knowledge is an important step in providing the basis for future research. It’s a huge leap forward in eliminating paralysis in patients who must undergo surgery with a 22% risk of postoperative paralysis.

While still a long way off, Dr. Awad says the day when he and surgeons around the world are able to assure their patients of a successful surgical outcome without the risk of paralysis would arrive sooner if the problem were better and more widely understood in the research community, as well as among the general populace.

“People are very much aware of the causes of heart attack, cancer, diabetes and other well-publicized diseases,” he says. “But very little is known about the common occurrence of aortic aneurysm and the risks associated with its surgery, the one and only treatment that is available to the patient. What we are doing to advance knowledge in this area is not enough. With more research funding, we could take these study results and focus on developing specific therapeutic interventions that could be tailored to the distinct pathophysiologic findings we now understand and begin to make real progress in developing new therapies and put an end to this game of chance we take each time we begin surgery.”

Dr. Awad and his team’s next steps are comparing the changes in nucleic acids, proteins and biochemicals they find in the animal models with those in the body fluids of the patients. They’re holding on to the hope that their findings will take future investigations a step closer to developing those new therapeutic interventions that his team anticipates.

To address the problem of the limited availability of human tissue for the study of spinal cord injury following aortic aneurysm repair, the team has a vision for the future that includes creating a multicentral clinical trials biobank in which to share human biospecimens and associated data with fellow scientists and practitioners around the world. It would serve as a guide for their preclinical research in aortic repair and offer a hopeful treatment plan to the growing number of aortic aneurysm patients.