Student-developed teaching module addresses historical and ongoing racist practices in medicine

Student-developed teaching module addresses historical and ongoing racist practices in medicine

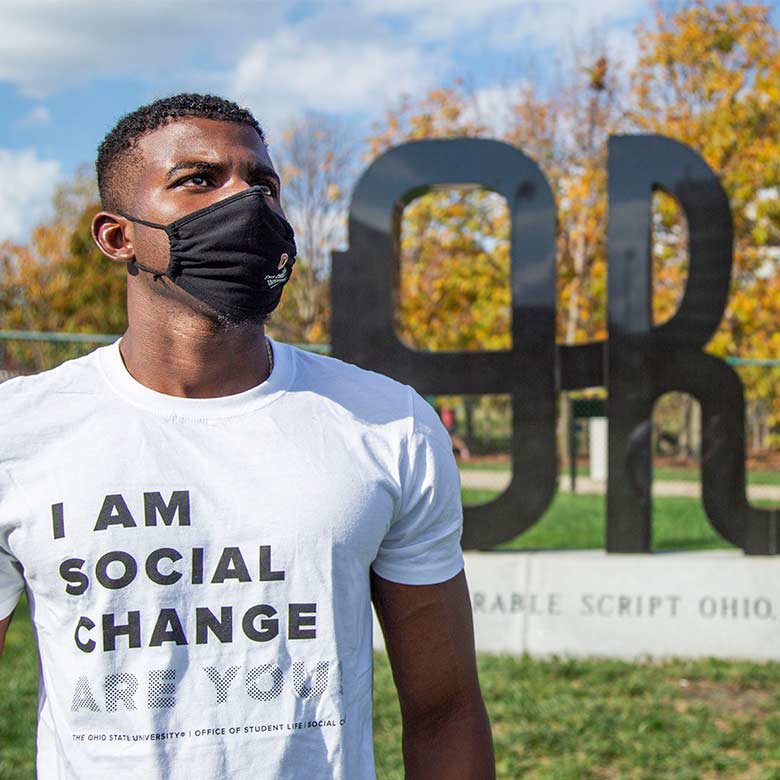

The lack of awareness and denial of racism within the profession of medicine relate in part to physicians not recognizing their negatively biased attitudes, perspectives and habits. Second-year medical students Hafza Inshaar, Abbie Zewdu and Deborah Fadoju stepped up to create an educational program for first-year medical students that explores the historical basis for some of the racist practices in medicine. With assistance from

Philicia Duncan, MD (external link), assistant professor of Internal Medicine, and

Valencia Walker, MD, MPH (external link), associate professor of Pediatrics, in The Ohio State University College of Medicine, they have uncovered a connection to current racial disparities observed in health outcomes.

The teaching module includes a pre-lecture survey to evaluate medical students’ knowledge and attitudes about racism and racist beliefs within the medical community. This is followed by a recorded lecture that discusses the origins of various medical myths about African Americans that have been passed on as medical truths, and their implications on equitable health care delivery.

Participating students are then asked to engage in thought exercises that utilize patient scenarios to illuminate the real-world, present-day consequences of racist teachings. These activities aim to identify the relationship between teachings and current practices, promote self-reflection to identify subconscious bias and stimulate group discussions on how health care workers can modify their viewpoints and forge change in the way that patients are currently treated. The goal is to ensure patients receive equitable and quality care regardless of racial/ethnic background. A post-lecture survey is used to gauge the impact of this lesson.

Knowledge of these racist and prejudiced medical myths can prompt students to recognize the ongoing harm they pose to the health of patients, and may encourage students to catalyze their awareness into action.

“This single lecture can’t solve the overarching issue of racism in medicine, and certainly won’t correct all of the gaps in the current U.S. medical education system, but it is a start,” the team said in a statement. “We hope that future coursework highlights the underlying societal drivers that cause medical disparities.”

Improving student care of sexual assault survivors through team-based learning intervention

About one in five women in the United States will be the victim of sexual assault in their lifetime, and the number is even higher in marginalized communities. For a patient, the road to psychological recovery from sexual assault can begin by disclosing the assault during a clinician-patient interaction.

To improve sexual assault education in the medical curricula,

Ashley Fernandes, MD, PhD (external link), associate professor of Pediatrics and associate director of the

Center for Bioethics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, and Amanda Start, PhD, director of the

Office of Curriculum and Scholarship at the Ohio State College of Medicine, teamed up with medical students Kylene Daily, Tiffany Loftus and Colleen Waickman. Together, they developed a student-led, team-based learning activity on how to provide effective care and support to sexual assault survivors.

“We integrated 45 minutes of sexual assault education content into a two-hour, pre-existing mandatory training on family violence for all fourth-year medical students,” says Loftus. “The sexual assault component included five core elements: the development of sexual assault learning outcomes, pre-work, knowledge assessment, an application exercise and a discussion centered around how the holistic care of survivors impacts their specialty of choice and their own self-care.”

The training includes learning outcomes designed to strengthen medical students’ abilities to effectively respond to sexual assault disclosures. This means providing holistic sexual assault care through humanistic communication and comprehensive patient advocacy. In designing the pre-work portion of the module, the team worked with a variety of sexual assault content experts to develop a brochure featuring information about sexual assault and society, empathetic interviewing, emergency department protocol, forensic nursing exam basics, surveyor resources, sexual assault in marginalized communities and the psychological consequences of sexual assault.

Students then complete an assessment that’s integrated into an existing team-based learning exercise on family violence. The assessment identifies common myths and stereotypes of sexual assault, and demonstrates effective emotional interviewing strategies. Students then demonstrate takeaways in the application portion through role-play scenarios and conclude the learning module with a 10-minute open discussion on future implications. To account for possible gender bias, the curriculum uses real-life cases of female physicians who made missteps in sexual assault care and questions that refer to male sexual assault survivors.

Student-developed teaching module addresses historical and ongoing racist practices in medicine

Student-developed teaching module addresses historical and ongoing racist practices in medicine