The expansion of telehealth at The Ohio State University was already underway, slated for a gradual, multiyear rollout.

Then COVID-19 hit.

“And with the pandemic, we realized that we didn’t have the luxury of waiting,” says L. Arick Forrest, MD, MBA, vice dean of Clinical Affairs for the Ohio State College of Medicine and medical director of Ambulatory Services for The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. “We needed to do something quickly.”

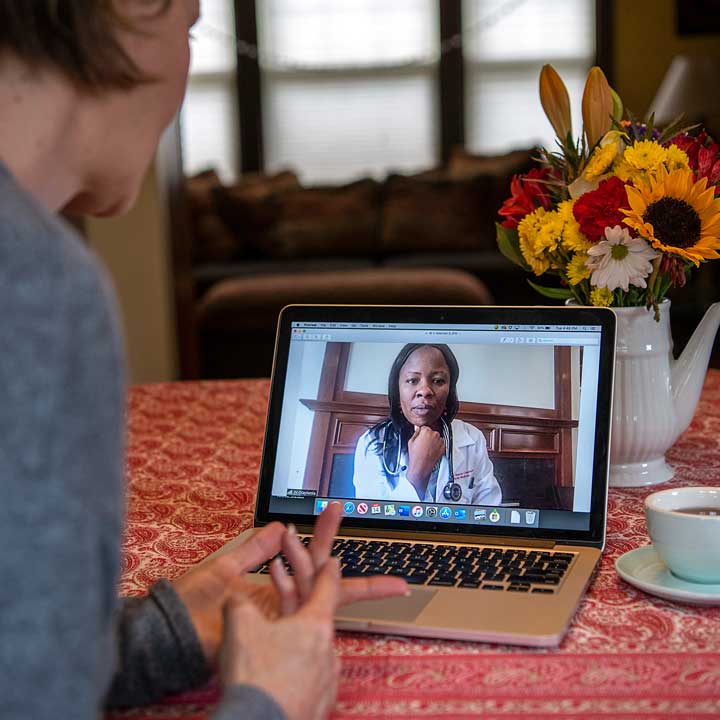

As schools and medical care facilities began to close and state officials advised residents to stay home for their safety, Ohio State launched a blitz of telehealth training and began deploying technology to enable remote visits. In just 10 days, 4,700 users, including physicians and other clinicians, were able to provide telehealth services, and the percentage of Ohio State clinicians across all specialties conducting telehealth visits skyrocketed from 2% to more than 95%.

“A major part of our mission is to improve people's lives, and we realized if we couldn’t reach out to patients in their homes, we couldn’t help them,” Dr. Forrest says. “This was the way we could connect to so many of our patients, whether they needed care for a common sinus infection or a consultation for a complex gastrointestinal problem. And that’s where our clinicians stepped up.”

At Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, remote visits went far beyond basic care. Telehealth was applied to a wide range of primary care needs, such as chronic disease management, physical exams, well-child visits, mental health follow-up, medication management, new patient encounters and acute non-emergent complaints such as back pain, headache and rash.

Specialists also leveraged telehealth to maintain high-quality care and trusted patient-doctor relationships, as well as to conduct electronic consultations with primary care clinicians for seamless specialty care. Otolaryngologist Brad deSilva, MD, says the technology proved particularly useful for speech and swallow therapy appointments. With the help of smart phones equipped with flashlights, he was also able to diagnose cancers of the throat, giving those patients the chance to begin treatment immediately, rather than waiting until COVID-19-related restrictions were lifted for a physical exam.

“Many of us were novices,” Dr. deSilva says, “but in five to seven days we were running a pretty large volume.”

At the peak of the pandemic, Ohio State was conducting 3,000 telehealth visits a day. Optimizing workflows became essential—care teams worked quickly to figure out the virtual flow of a patient visit that preserved the high-quality experience. A multi-disciplinary telehealth workgroup led a remarkable series of efforts addressing various technical, clinical, training, logistics, process, communications and workflow needs.

“Telehealth went from being a cool innovation that some people used, to something that was really a necessity for everyone,” says J. Nwando Olayiwola, MD, MPH, chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine. “We had so many people invested in making sure we were successful from across the medical center.”

Family and Community Medicine. “We had so many people invested in making sure we were successful from across the medical center.”

That success meant the medical center’s telehealth effort became a model for others. Academic health centers as far west as Stanford University, as well as in-state health organizations, sought advice from Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, especially related to patient trust and understanding—where the medical center excelled. Patients scored

their telehealth experiences incredibly high, and even those who had been reluctant to use digital tools such as MyChart were able to pivot to a new way of seeing their physicians. No-show rates were cut by half.

“Some of my patients don’t like technology that much,” Dr. Olayiwola says. “It’s amazing to see how well so many of them adapted.”

Telehealth also seemed to eliminate the hierarchical barrier between clinician and patient by putting each on equal footing, Dr. Olayiwola says.

“In the traditional in-office experience, you are in my exam room where I examine you and have all the power and all the control,” she says. “Now we’re both inviting each other into each other’s space. People in their homes are completely different—you see their dog running around or their cat on their lap, and they’re smiling or interacting with other people in the home. A lot of my patients are so much more relaxed.”

The learnings from the COVID-19 era of telehealth will inform the future of the broader telehealth program at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, both in its practice and teaching of future physicians. The goal, Dr. Forrest says, is to be a leader in telehealth education and make telehealth less of an urgent care vehicle, integrated more into primary and specialty care.

Key developments will include not only standardizing best practices for telehealth exams and care, but customizing individual telehealth experiences through the use of home monitoring equipment—positioning telehealth not as a replacement for traditional care, but as an enhancement with limitless possibilities. Dr. Olayiwola says the medical center will also work to close the “digital divide” by addressing critical inequities that may inhibit a patient’s access to telehealth care, including the lack of a suitable electronic devices or reliable internet service, lower health and telehealth literacy, language barriers and disabilities requiring additional accommodations.

While the original plan for expanding telehealth might not have gone as desired, both Dr. Olayiwola and Dr. Forrest say it was a success rooted in early preparation, institutional readiness, nimble clinician thinking and impressive patient support.

“The way we approached it,” Dr. Forrest says, “was this: We have this crisis in front of us—let’s make it as positive of an experience as possible for our patients and care teams.”