Special art exhibit and panel discussion shed light on burnout and suicide risk in physicians and health care providers

“I can’t do this anymore; it’s not good for me.”

“I can’t do this anymore; it’s not good for me.”

– Scott Jolley, MD. Family members and colleagues shared his story with artist Jeremy Rosario.

Burnout and suicide risk among physicians and health care providers across the United States continues to be a serious issue.

Take, for example, Scott Jolley, MD, who was an emergency medicine physician in Utah when his grueling schedule led him to repeatedly ask his employer to lighten his workload. He was an aging physician in a fast-paced specialty, and he was facing burnout. Unfortunately, his pleas went unanswered. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. His workload increased, as did his stress level.

Dr. Jolley took an unpaid sabbatical to seek outpatient mental health care, though he feared the stigma that awaited him after reaching out for care. Days after being discharged from an inpatient stay in the psychiatric unit at the hospital where he worked, Dr. Jolley lost his life to suicide.

Sadly, compassion fatigue – the emotional cost of caring for others – is a major contributing factor to stress, burnout and suicide risk in health care. According to the American College of Emergency Physicians, roughly 300 to 400 physicians die by suicide each year in the United States, and more than half of physicians know a colleague who’s considered, attempted or died by suicide.

Earlier this month, a group of clinicians and leaders from The Ohio State University College of Medicine gathered for a panel discussion organized by the Gabbe Well-Being Office to honor the National Physician Suicide Awareness Campaign and National Suicide Prevention Month.

Carol R. Bradford, MD, MS, FACS, dean of the Ohio State College of Medicine, says visibly demonstrating a willingness and desire to address mental health is key to building trust and protecting against burnout in the profession.

“Listening actively, without judgment, and responding with genuine care and concern shows our colleagues, our learners and the patients and families we serve that they are understood and supported,” Dr. Bradford says. “It shows them that they can always count on us to be there for them.”

Addressing the acute mental health crisis among healthcare providers

At the event, Andrew Thomas, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, shared with the audience that he lost a close friend to suicide while they were both in medical school, which led him to commit to paying closer attention to colleagues and looking deeper into changes in behavior and disposition. This has turned into a career-long effort to be present and supportive of others.

“There is a lack of understanding of what is going to happen if I raise my hand and say, ‘I need help,’” Dr. Thomas says. “The way we take care of our providers is by treating addiction and mental health as an illness, not a character flaw.”

K. Luan Phan, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at the College of Medicine, says that the gap between burnout, stress and suicide is much smaller than we might imagine.

“We keep our struggles quite internal because of our sense of pride and guilt,” Dr. Phan says. “We think, ‘I can’t admit that this is happening to me, it isn’t supposed to happen to me.’”

Drs. Thomas and Phan both emphasized that seeking help is never a sign of weakness. Far too often, suffering in silence leads to loss of life. In tandem with the panel discussion, the event included a special art exhibition, “The Disposables,” a project launched by the global coalition, Disappearing Doctors, founded by FCB Health New York.

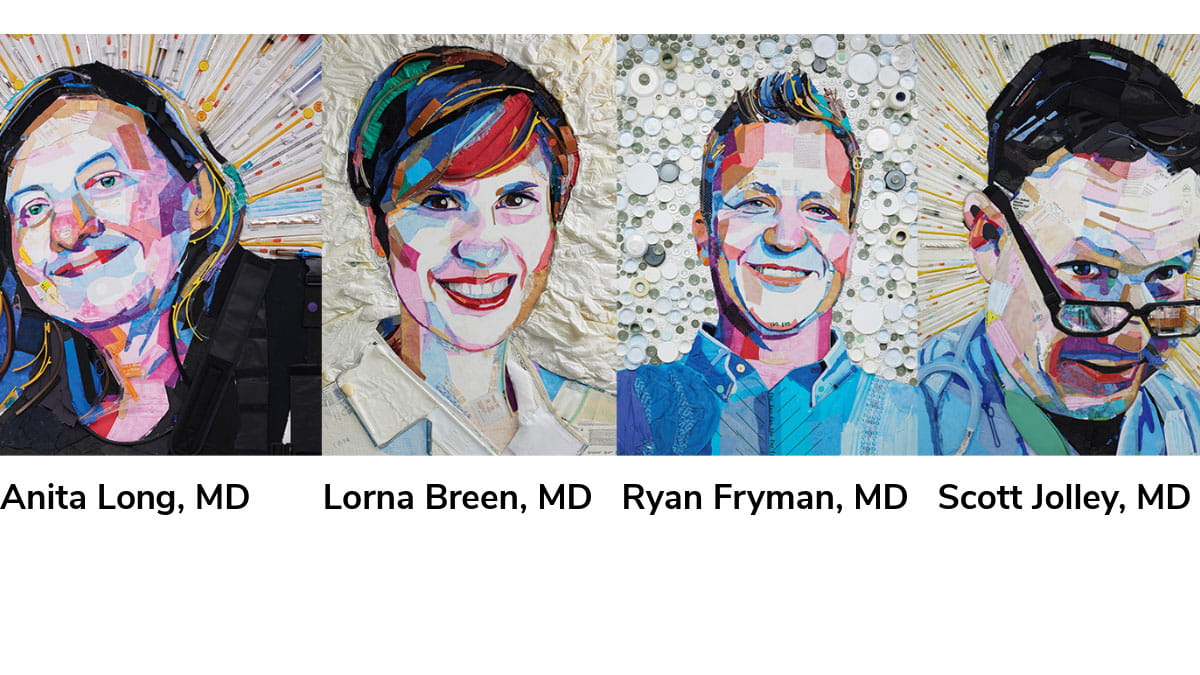

Artist Jeremy Rosario from Delaware, Ohio and vice president and creative director at FCB Health New York, crafted the breathtaking portraits on view using paint and donated disposable medical materials used by physicians everyday. During the panel, he shared that physicians use stethoscopes, their hearts and their education and training to save lives. He believes we need to pay better attention and learn to recognize what’s going on underneath the façade these professionals put on for their colleagues.

“We’re listening to our team members diagnose and treat patients, but we are not listening to them on the other side of the stethoscope,” Rosario says.

Laxmi Mehta, MD, clinical professor of Internal Medicine, chief well-being leader and faculty director of the Gabbe Well-Being Office, says working alongside health care teams adds more voices and observations to the mix on team member well-being and mental health status. She says it’s important to give grace to others and step in to help them when they can’t advocate for themselves during a tough time.

“Someone on the team may notice someone struggling and point it out to you,” Dr. Mehta says. “Or you may hear them commenting that someone is acting differently than usual.”

Normalizing the need to process workplace stress

Arianna Galligher, MSW, LISW-S, is director of the Stress, Trauma and Resilience (STAR) Program and program director of the Gabbe Well-Being Office at the College of Medicine. As the panel moderator, she shared STAR’s proactive approach to normalize the very human need for health care professionals to process the pain that arises in their work. She says the inherent stress and trauma of losing patients and navigating difficult conversations, all while managing their own personal responsibilities, creates an increased need for support among these professionals. She noted that this support should center around changing and improving intentional conversations and practices that normalize these experiences.

One option is the STAR Brief Emotional Support Team (BEST) training, which uses evidence-based techniques to equip participants with the necessary skills and resources they need to have intentional conversations with their colleagues and peers who might be in crisis.

“Normalizing distress reminds us and others that it makes sense to be thrown for a loop, even when we do everything right and we don’t get the outcome we wanted or expected,” Galligher says.

As does reminding everyone to take time to care for themselves and their team members.

“This entails not being so prescriptive and building the capacity to feel comfortable relying on others,” Dr. Mehta says. “This way we are not alone. That is half the battle.”

Building a coalition of support

Anita Lang, MD, an alum of the College of Medicine, was an assistant professor at a different medical school at the time of her death. Her daughter, Jordan Lang Taylor, says she was a “beacon of hope” for her patients. Dr. Lang tried to share that she was struggling and get help to address her well-being. Yet, Lang Taylor describes the dissonance her mother faced.

“A doctor is supposed to fix other people versus being fixed,” Lang Taylor says. “Where do you go for help?”

You go to others. You embody openness and intentional listening. Dr. Thomas says you step in when we notice our team members are not clicking like they usually do and ask probing questions.

Rosario’s work builds beautiful portraits of those lost. This project serves as a beautiful memorial and creates immediacy around a dialogue about mental health and available resources.

“We need to lean in on these difficult conversations,” Rosario says. “And build a coalition and an intentional community to solve this.”