Students develop teaching module addressing historical and ongoing racist practices in medicine

Racism is a multifaceted issue, manifesting in various ways through socioeconomic and medical climates. Contrary to the “do no harm” pledge sworn by physicians, the medical community is not impervious to the racist attitudes and actions normalized by society. Explicit and implicit bias, microaggressions and stereotypes continue to foment inequality in health care delivery and patient outcomes. The tangible proof lies in the patterns of Black patient outcomes as they experience higher death rates, lower specialty referrals, a shorter average lifespan and higher incidences of chronic illness and infection.

Racism is a multifaceted issue, manifesting in various ways through socioeconomic and medical climates. Contrary to the “do no harm” pledge sworn by physicians, the medical community is not impervious to the racist attitudes and actions normalized by society. Explicit and implicit bias, microaggressions and stereotypes continue to foment inequality in health care delivery and patient outcomes. The tangible proof lies in the patterns of Black patient outcomes as they experience higher death rates, lower specialty referrals, a shorter average lifespan and higher incidences of chronic illness and infection.

With national and local recognition of systemic racism as a public health crisis, health care stakeholders are working to address this issue by its root causes. The Ohio State University College of Medicine pledges to stand against the consequential institutionalized racism and the injustices generated by such a system. One of the many ways the college is addressing racism is through a student-developed teaching module that dispels the racist medical myths about African Americans.

Raising awareness in medical education to tackle racism

The lack of awareness and denial of racism within the profession of medicine relates to physicians not recognizing their negatively biased attitudes, perspectives and habits. Many physicians never learn about the historical use of science and medicine to justify racist beliefs and practices. Rectifying these knowledge gaps and teaching ways to decrease negative implicit biases represent some useful strategies for medical students to help mitigate racism in health care.

Second-year medical students Hafza Inshaar, Abbie Zewdu and Deborah Fadoju created an educational program for first-year medical students that adds invaluable content to the current medical school curriculum. Their program explores the historical basis for some of the racist practices in medicine and highlights the connection to current racial disparities observed in health outcomes.

“When we were in our Reproductive Disorders block, we were shocked to see that there was no mention of the stark disparities in maternal and infant mortality,” the team said in a statement. “We firmly believe that mentioning race-based medical disparities without meaningful discussions of the context by which these disparities were created or the social drivers that perpetuate them is not just insufficient, it’s negligent.”

They received assistance from two faculty members at Ohio State College of Medicine, Philicia Duncan, MD, assistant professor of Clinical Medicine, and Valencia Walker, MD, MPH, associate professor of Pediatrics.

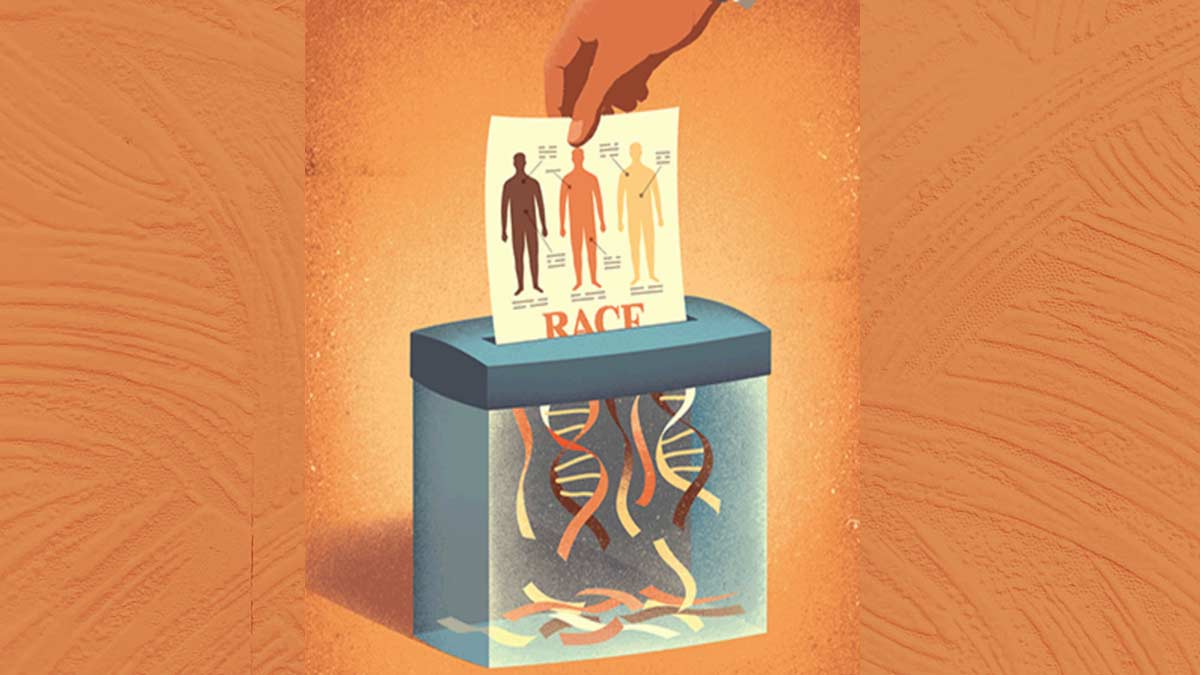

“Human race is a powerful illusion with intractable irony,” Fadoju says. “Race, a social construct devoid of any biological meaning or genetic root, has managed the power to produce palpable impact. This painful irony is one that medicine and medical education must address and meaningfully consider in efforts to produce racial equity. We hope this is a start.”

The teaching module includes a pre-lecture survey to evaluate medical students’ knowledge and attitudes about racism and racist beliefs within the medical community. This is followed by a recorded lecture that discusses the origins of various medical “myths” about African Americans that have been passed on as medical truths, and their implications on equitable health care delivery.

“Blacks have lower lung capacity than whites, Blacks have higher pain tolerance than whites and Blacks are lazy, ignorant and aggressive are all myths,” the team said in a statement. “Our presentation explores the historical origins of these myths, then ties these misconceptions to their present-day medical impact such as the use of inaccurate race-based spirometers and disparities in pain treatment.”

Participating students will then be asked to engage in thought exercises that utilize patient scenarios to illuminate the real-world, present-day consequences of racist teachings. These activities aim to identify the relationship between teachings and current practices, promote self-reflection to identify subconscious bias and stimulate group discussions on how health care workers can modify their viewpoints and forge change in the way that patients are currently treated so they receive equitable, quality care regardless of their racial/ethnic backgrounds. A post-lecture survey is used to gauge the impact of this lesson.

“This year, we are adding our teaching module to the Endocrine and Reproductive Disorders block. It might be moved earlier in the academic year in the future, but it will continue to remain a part of the M1 curriculum,” says Inshaar.

The team hopes that this program will reform faculty perspective as well.

“Beyond providing education to students, I hope to support faculty development initiatives that improve faculty understanding about these issues and help them add relevant content to their teaching modules,” says Dr. Walker.

Future room for curriculum reform

Knowledge of these racist and prejudiced medical myths can prompt students to recognize the ongoing harm they pose to the health of patients, and may encourage students to catalyze their awareness into action. The team notes that to ensure a lasting impact, the themes of this teaching module should be better incorporated into all teachings.

“While I agree that this topic deserves special attention, separating it from the ‘main curriculum’ leaves the impression that it’s a specialty of medicine reserved for only those interested in the topic of health inequities,” Dr. Duncan says. “We need to impress upon our medical students that addressing racism in medicine is important to all faculty members across all specialties. This topic needs to be interwoven into all lectures within the curriculum, rather than added on.”

They also stress the importance of continued action.

“This single lecture can’t solve the overarching issue of racism in medicine, and certainly won’t correct all of the gaps in the current U.S. medical education system, but it is a start,” the team said in a statement. “We hope that future coursework highlights the underlying societal drivers that cause medical disparities.”

Through acknowledging and improving upon these flaws, the Ohio State College of Medicine will produce physicians who are better equipped to ensure health equity among all patients.