You only have five ventilators left and 10 patients in respiratory failure. What will you do?

You only have five ventilators left and 10 patients in respiratory failure. What will you do?

That’s just one of the case scenarios medical students are asked to consider in a newly redesigned course to prepare them for residency training during the unique conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Developed at lightning speed with multidisciplinary input from faculty across The Ohio State University health science colleges—medicine, ethics, pharmacy, veterinary medicine and public health—the course combines features of previous disaster medicine courses with a primary focus on treating COVID-19 patients.

“Today, disaster response requires a different mindset,” says Nicholas Kman, MD, professor of Emergency Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. “We must move from a mode of taking care of individual patients to taking care of the population as a whole. So we had to redesign the course.”

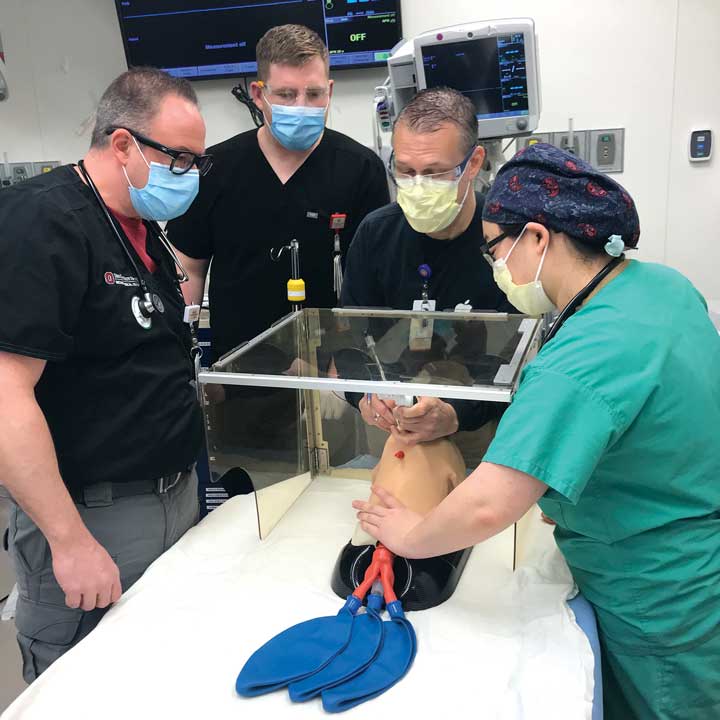

Basic safety practices are now supplemented with instruction on donning and doffing personal protective equipment (PPE) and decontaminating equipment when exposed to chemicals. Designed to develop critical thinking and judgment skills, the course uses a type of incident response playbook that models the spread of an infectious disease as well as scenarios that Dr. Kman implemented during COVID-19.

“Doctors often grapple with difficult ethical decisions when responding to pandemics like COVID-19 and mass casualty events,” he says. “This course provides an opportunity for medical students to learn not only best practices for disaster management but also how to manage the psychosocial pressures of caring for large numbers of patients with serious medical issues.”

Named “Pandemic and Disaster Medicine: COVID-19 Response From the Bedside to the Federal Level,” the new course was initially offered to graduating seniors and other medical students who were eager to serve but who—like fellow trainees across the nation—had been locked out of their traditional third- and fourth-year clinical rotations due to COVID-19 precautionary safety measures.

Along with early graduation and licensing to practice, the training made it possible for these students to serve in hospitals and clinics in advance of the start of their residency program training, while earning 10 hours of course credit. Some were able to assist Ohio State’s COVID-19 call center—one of the state’s leading help lines—discussing symptoms and answering questions of concerned citizens around the state. This experience provided students with a unique insider’s look into how the COVID-19 response was developing. Others helped prepare test kits at The Ohio State University Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute. And others assisted the Centers for Disease Control with contact tracing.

One graduating senior was asked by the chief medical officer for the Oklahoma City Area of Indian Health Service to assist their statistician in monitoring testing rates across the region and to help public health nurses monitor contacts and resource allocation at the agency’s regional incident command center. Another senior was able to assist the Maricopa County Department of Public Health in Arizona with investigating the state’s exposure response to the area’s first case of COVID-19.

“At Ohio State, we’ve been teaching disaster medicine for some time now,” says Daniel Clinchot, MD, vice dean for Education. “But our team’s ability to quickly pivot to COVID-19 education allows our students to gain strong pandemic skills, so they’re fully prepared to enter the real world and offer expertise as new graduates.”