Ohio State scientists earn top program grants for translational research

The National Institutes of Health’s Research Program Project Grants (P01) support broad, long-term programs that involve three or more groups of investigators working on separate research projects that contribute to one overall objective.

P01 grants are the gold medals of research. Highly competitive and selectively awarded, these large grants – often awarded in sums in the tens of millions of dollars – elevate the reputations of the associated institutions.

“The P01 grants not only allow us to bring together individuals with complementary expertise, but they also provide financial support for those expertise ‘cores,’ which house different scientific areas of interest,” says Rama Mallampalli, MD, chair of the Department of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Dr. Mallampalli has earned an $11.6 million P01 grant for his five-year investigation to find a new therapy to stimulate the immune systems of patients who have developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) from severe pneumonia.

“The grants are difficult to get because it’s difficult to achieve that synergy among multiple research groups,” says Electra Paskett, PhD, the Ohio State University Marion N. Rowley Professor of Cancer Research, director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control in Ohio State’s College of Medicine, and associate director for Population Sciences at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute.

Paskett would know: Her public health initiative has been awarded an $11 million P01 grant to test prevention programs to address elevated rates of cervical cancer in Appalachia. The five-year research project involves clinics in health systems across four states using four principal investigators, 25 faculty-level investigators and additional external consultants.

Ohio State’s uniquely multidisciplinary research model is especially supportive of that synergy – Ohio State faculty, staff and students are accustomed to approaching research from multiple, complementary areas of focus and collaborating among different health sciences colleges.

Influencing the future of health care

Dr. Mallampalli and Paskett’s projects both aim to identify solutions for problems that impact large populations of patients.

ARDS affects about 200,000 Americans each year, and patients with ARDS face a high mortality rate – as high as 46 percent.

The American Cancer Society estimates that, in 2019, about 13,170 new cases of invasive cervical cancer will be diagnosed, and about 4,250 women will die from cervical cancer. The region Paskett’s team is studying has one of the highest rates of cervical cancer and cervical cancer deaths in the United States.

Dr. Mallampalli and Paskett both look forward to finding solutions for patients that can be implemented as quickly as possible, leveraging the strong relationships their investigators have developed over years of collaborating with one another and with other universities.

More about Dr. Mallampalli’s project

Despite decades of intense study of the initial, inflammatory phase of ARDS, mortality rates are still high because new pharmacotherapies haven’t emerged to treat the condition. Dr. Mallampalli’s program project challenges the concept that ARDS is solely a hyper-inflammatory disorder and instead focuses on the immunosuppression that manifests in ARDS patients.

“This looks at new ways by which people with severe pneumonia lose their immune defense system,” Dr. Mallampalli says. “Often, they’re immunosuppressed like cancer patients, and this P01 will be providing resources to identify new targets that will serve as a platform for designing new compounds or drugs that can be used to stimulate the immune system to combat infection.”

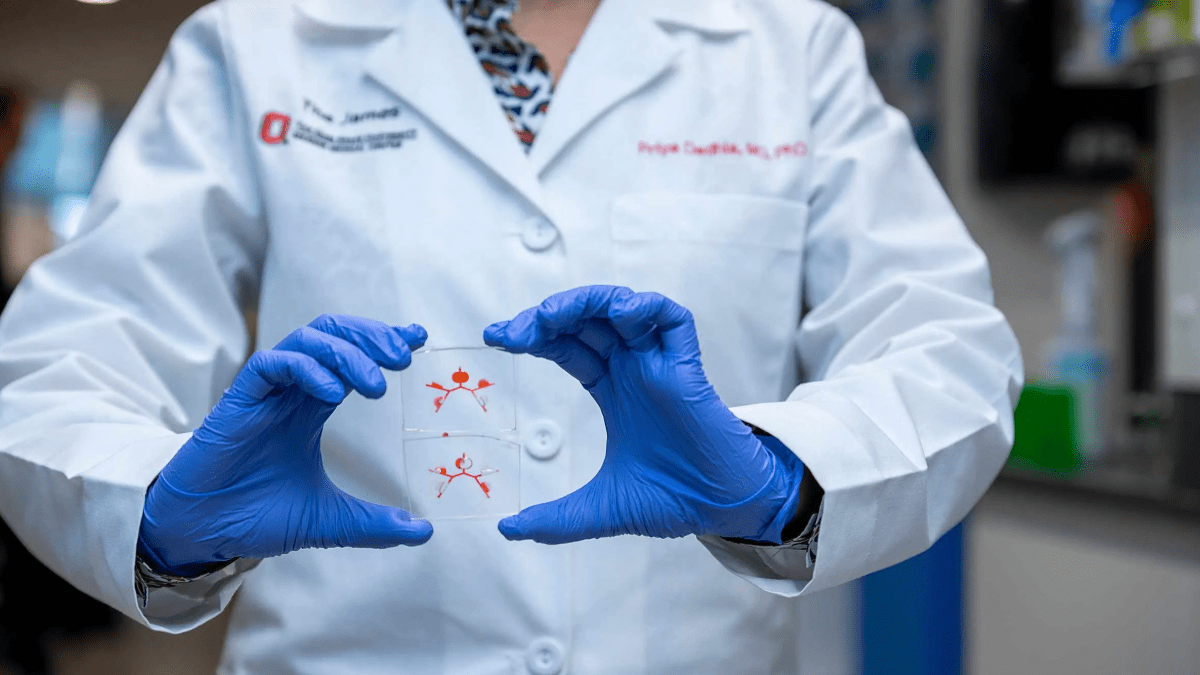

To evaluate this hypothesis, researchers supported by cores of experts in bioimaging and human biorepository services will use state-of-the-art molecular, cell, human-based systems and lipidomic tools in human subjects with ARDS. Their work could create a paradigm-changing model for ARDS pathogenesis, changing the way ARDS therapies are studied and developed in the future.

“What I’d like to see happen over the number of years is that we identify a novel protein that can serve as the basis for analyzing that protein’s behavior to eventually design, synthesize and test new immunomodulatory compounds for patients with severe pneumonia,” Dr. Mallampalli says.

More about Paskett’s project

The goal of Paskett’s program project is to create a clinic-based integrated prevention program that focuses on the major causes of cervical cancer: tobacco smoking, human papillomavirus infection and lack of cervical cancer screening. Her team will present a family-focused cancer-risk reduction program within federally qualified health clinics in 10 health systems in Ohio, Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia.

“What’s exciting to me is that we’ll be going into each of these clinics and personalizing how this intervention rolls out in each clinic based on their staff and their community,” Paskett says. “We’ll identify what works best, capitalize on their strengths and give tips.”

Paskett, who has studied cervical cancer for 35 years, explained that the project is testing a novel strategy of bundling prevention services and using implementation science to address healthcare disparities in underserved populations such as those in Appalachia. It’s designed to target the individual, social, community health system and broader contextual-level barriers related to the burden of cervical cancer.

The interventions the team creates will be offered to eligible female patients and age-eligible children and young adults in the region. They’ll then test the effectiveness of the integrated cervical cancer prevention program and evaluate the impact of the program, including implementation and acceptability, with attention to short- and long-term impact and sustainability.

“By creating solutions that are sustainable after we leave, we’ll be able to reach a lot more people through the clinic staff as part of their routine care than we could for any of our other studies, which were individual-level, randomized trials,” Paskett says.