Determining readiness for rehabilitation in spinal cord injury

Approximately 291,000 people in the U.S. suffered traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) from accidents, violent acts, sports and recreational activities or medical and surgical complications in 2019. An additional 17,730 or more new cases are expected each year thereafter, according to statistics published by the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. The consequences of traumatic SCI can be severe, resulting in permanent or partial paralysis. Recovery from SCI is lengthy and is typically quite limited.

Approximately 291,000 people in the U.S. suffered traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) from accidents, violent acts, sports and recreational activities or medical and surgical complications in 2019. An additional 17,730 or more new cases are expected each year thereafter, according to statistics published by the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. The consequences of traumatic SCI can be severe, resulting in permanent or partial paralysis. Recovery from SCI is lengthy and is typically quite limited.

Unfortunately, damage to the spinal cord from injury can’t be reversed, so current research focuses on the development of methods to improve functional recovery using physical rehabilitation, sometimes in combination with other treatments.

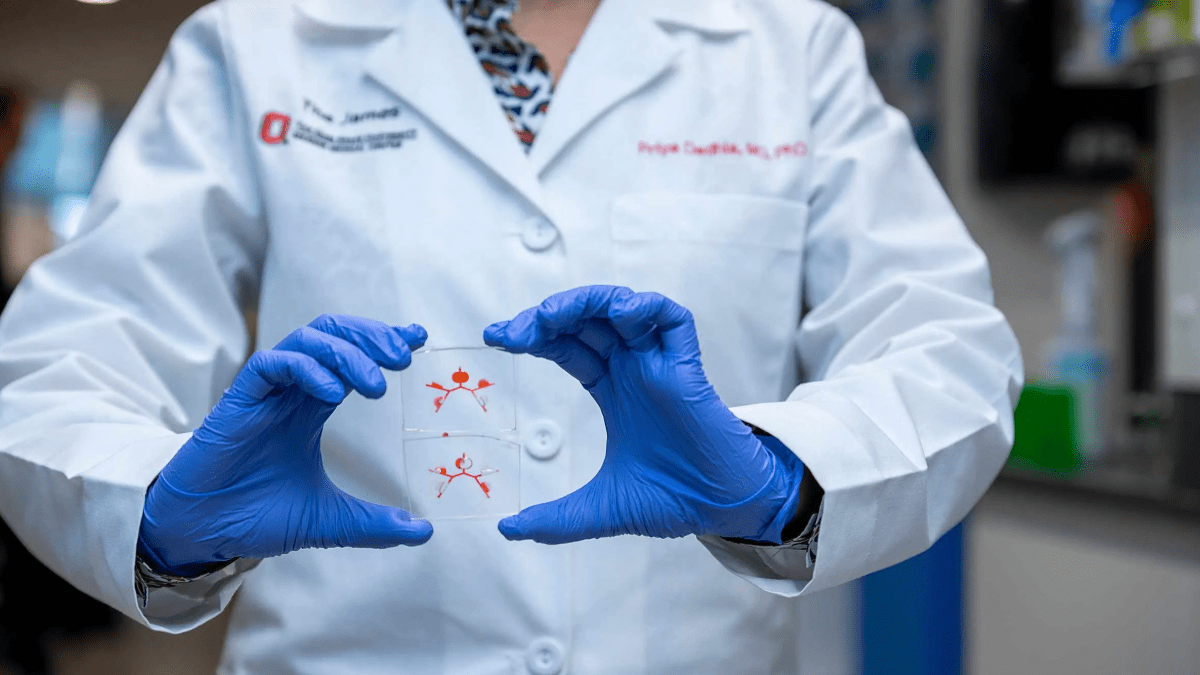

One such study is underway at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, led by D. Michele Basso, EdD, PT, professor and associate director of the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the school’s director of research. The study is funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense and will test a novel combination of nerve-muscle stimulation and walking training on a downslope treadmill. Each therapy has been found separately to increase activation and movement beyond what is possible with traditional rehabilitation.

Therapies that are individually effective, however, do not ensure recovery when combined, cautions Dr. Basso.

“Treatments delivered too early may actually interfere with, rather than assist, recovery based on our preclinical studies. Therefore, we will also study genetic and MRI imaging markers as ‘go or no go’ thresholds to determine readiness for this combined, more potent form of rehabilitation,” she says.

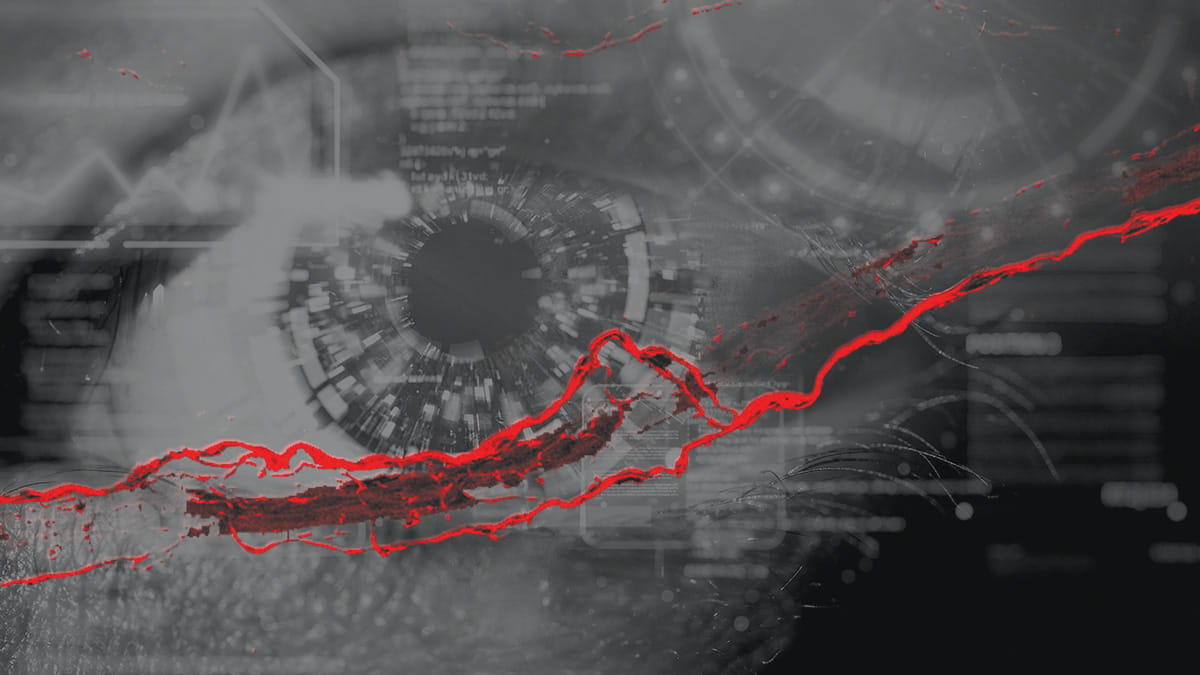

Dr. Basso explains that the optimal time to begin therapy can be determined by the level of inflammation and loss of myelin, the insulating layer surrounding the nerves in the brain and spinal cord. Studying genetic and MRI imaging markers will allow the team to identify a window of time when potential barriers to recovery are minimal—specifically when inflammation is low and myelin loss is still limited. By minimizing barriers, the brain and spinal cord may respond optimally to new rehabilitation interventions, and recovery may be much more extensive.

Once an optimal intervention time has been established, the team will begin therapy using the combination of the two interventions of downhill walking and muscle-nerve stimulation. Downhill walking is a hard task that makes muscles work in a different way, like shock absorbers, to control descent and avoid jarring. Nerve and muscle stimulation activates the muscle in precise patterns, making up for low or absent muscle function early after injury.

“Using the combination of these approaches for rehabilitation may promote greater functional recovery in people with SCI,” says Dr. Basso. “We think that if the treatment works, someone with SCI will regain the ability to do difficult tasks with precision and control—relearning the best parts of the two treatments.”