New Clinical Study to Evaluate Immune Responses of Pregnant Women to TdaP Booster Vaccination

Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is a highly contagious, life-threatening respiratory disease caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis that hospitalizes approximately 15,600 adults and 1,000 infants each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Infants are most at risk for severe, life-threatening complications from pertussis, including pneumonia, convulsions, brain damage and death.

Pertussis, also known as whooping cough, is a highly contagious, life-threatening respiratory disease caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis that hospitalizes approximately 15,600 adults and 1,000 infants each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Infants are most at risk for severe, life-threatening complications from pertussis, including pneumonia, convulsions, brain damage and death.

The CDC currently recommends immunizing pregnant mothers with the Tdap booster vaccine at 27 – 36 weeks gestation. Epidemiological studies and animal model investigations suggest that newborns are protected from pertussis if their mothers are vaccinated during pregnancy—because antibodies generated in the mother are transferred to the fetus and protect infants from whooping cough before they are old enough to receive the DTaP infant immunization.

Prior to 1997 all infants received the whole cell vaccine (wPV), which provided long-lived protection, but also sometimes had severe side effects. Acellular vaccines (aPV), which contain proteins from B. pertussis along with the alum adjuvant, were developed in the 1990s and became standard of care in the U.S. in 1997. Women of child-bearing age, who may have received either of these vaccines as infants, are offered the Tdap booster during pregnancy. The responses of the pregnant women themselves to the Tdap booster are poorly understood.

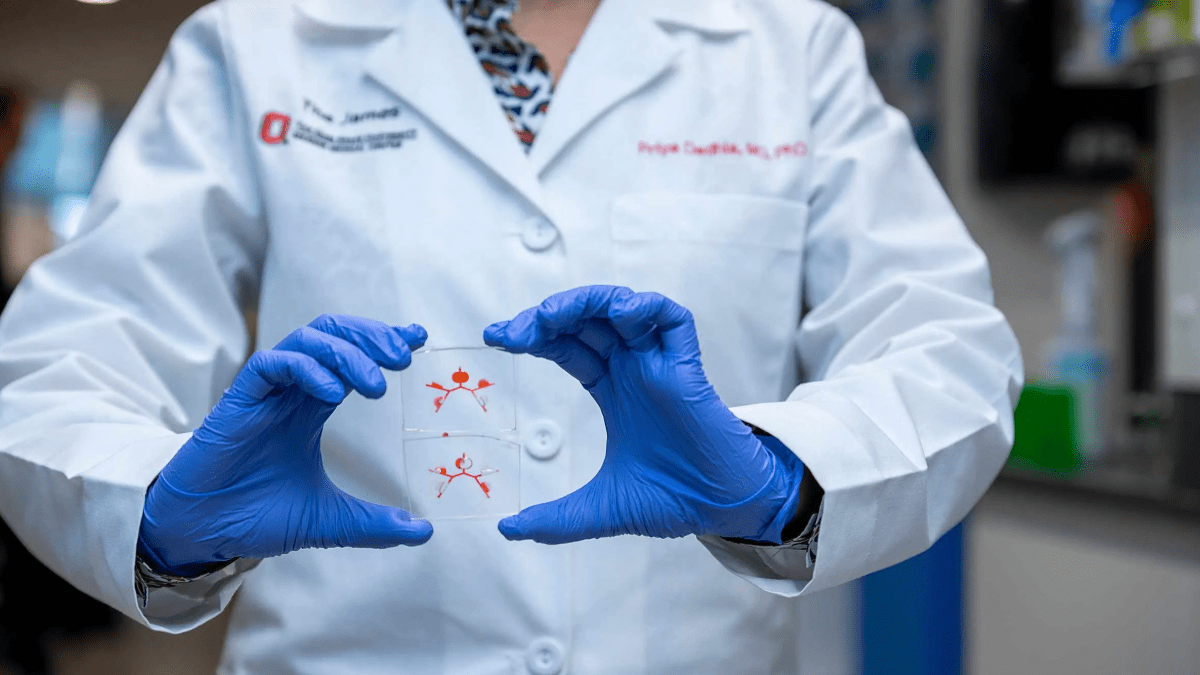

A team of researchers led by Purnima Dubey, PhD, and Brett Worly, MD, at The Ohio State University College of Medicine hope that their recently funded study will shed light on this important question by comparing the responses of pregnant women born before 1997, who were vaccinated with wPV, and pregnant women born after 1997, who were vaccinated with aPV as infants. Looking at women who have received these different vaccines in the past, the Ohio State team will examine the quality of the pertussis-specific immune response generated in their pregnancies to understand the molecular mechanisms at play that protect the infant and the mother.

Dr. Dubey, who is an associate professor in Ohio State’s Department of Microbial Infection and Immunity and principal investigator in the study, explains the science behind the work. “CD4+ helper T cells are the major component of the adaptive (learned) immune response and provide help to B cells that produce antibodies. The molecules that the T cells produce after vaccination shape the quantity and quality of the immune response and the protection against infection,” she says. “We will study the composition of the T cells generated in pregnancy before and after Tdap booster, and will compare them to responses in nonpregnant women with the same immunization history. Our comprehensive study will also evaluate the quantity and function of the antibodies generated by the booster vaccination. We hope that this study will provide mechanistic understanding of Tdap vaccine-induced immune responses during pregnancy that may inform clinical care of pregnant women.”

The team will begin recruiting patients for the study this fall in the Ob/Gyn resident clinic. The two-year cohort study is funded by a $630,000 contract awarded to Drs. Dubey and Worly by the CDC.