Standardized patients play integral role in medical student education

Mary reviews the medical cases on the briefing document: Tachycardia. A collapsed lung following a car accident. Last week, she played a patient presenting in the emergency department with symptoms of stroke.

“I acted out the physical aspects of what happens, the face droop, all of it,“ she says. “It’s so important for the medical students to see and hear what that looks like in real-time.”

Working at the intersection of classroom and clinic, Mary is trained to role-play ill and healthy patients alike so medical students can gain hands-on patient experience. Sometimes the patient has no specific findings, which allows the learner to practice a variety of communication and examination skills.

Mary works part-time as a Standardized Patient (SP) at The Ohio State University College of Medicine’s Clinical Skills Education and Assessment Center (CSEAC). She considers herself an amateur actor, participating in local theater, but having acting or medical experience isn’t required for the job.

“You just have to be curious and be able to learn quickly,” says Ann, who’s been an SP for the past 12 years. “It’s really rewarding to witness a student having an aha moment in a safe environment where they’re practicing and learning from each patient encounter.”

The CSEAC is a state-of-the-art training center simulating actual patient care experiences. The SP program enables students to see patients with the illnesses they are studying, melding classroom learning and clinical education as early as their first year. Although the first-year medical students, or M1s, don’t know ahead of time what’s wrong with their patient, they do know they’re trained and sometimes follow scripts to direct the examination.

“It’s not a “got-you” scenario, it’s organized and controlled,” says Jonathan Zhou, an M1. “You learn to ask the right questions, work on personal skills and build confidence.”

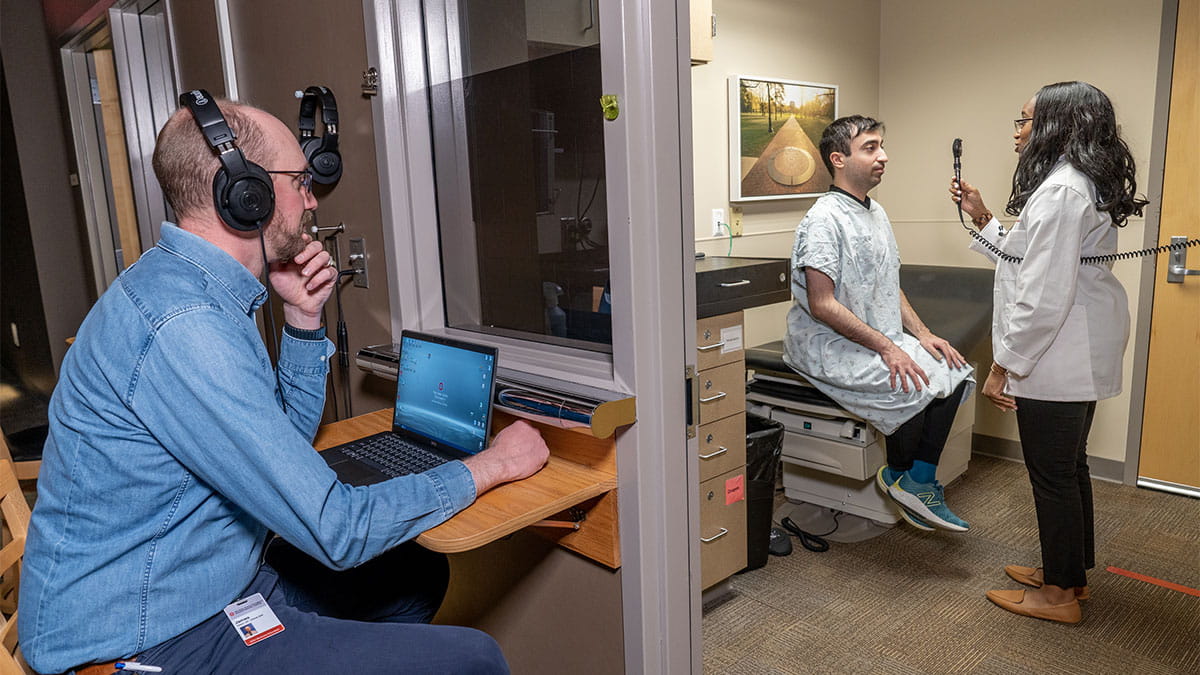

The SP space is a high-tech suite of 14 examination rooms stocked with equipment typically found in a doctor’s office. Each room has a camera and a one-way glass observation window where faculty view encounters with SPs from outside the room.

Jay Read serves as the associate director of the CSEAC. He says the set-up allows for faculty to assess learners’ skills as part of their education and provide constructive feedback on communication and interpersonal skills and more technical aspects of their patient interaction.

“It’s really important to have a diverse group of SPs in our rotation so students work with patients of all ages, backgrounds and identities,” Read says. “This provides better perspective on unique presentations in a variety of patient populations.”

SPs also work with medical students, residents and faculty in the simulation and procedures space, which is a 3,000-square-foot training lab complete with four virtual critical care and surgery bays with observation and control stations and an ultrasound room. Here, the stakes can be much higher for students who’ve progressed further through the curriculum. Often these medical simulations are graded based on diagnostic and treatment decisions they make while working in a simulated emergency situation.

Read says there are between 700-750 SP events each year, which is why they’re constantly recruiting community members for the paid position.

“It’s a really great job for students, retired folks and gig workers who have some flexibility and can manage a varied work schedule” Read says. “We also cover parking, which really helps.”

Mary and Ann both report that their schedules can vary from week to week. “Some weeks I do 30 hours and others just a few,” Ann says. “I love it.”

Anyone age 18 and up and of any racial, ethnic, or religious background, as well as those of any ability, gender, or sexual orientation, are encouraged to apply and play a role in educating future generations of medical providers.