Schnyder Corneal Dystrophy

Schnyder corneal dystrophy effects about 320 people in the United States. Two of them are patients at the Ohio State Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. 26 years ago, Laura Booth came to The Ohio State University Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences with vision worsening more than normal for her age. She was diagnosed with a rare genetic disease called Schnyder corneal dystrophy—where crystals cloud the corneal stroma and progressively decrease visual acuity. Her sister Cathy was diagnosed soon after.

26 years ago, Laura Booth came to The Ohio State University Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences with vision worsening more than normal for her age. She was diagnosed with a rare genetic disease called Schnyder corneal dystrophy—where crystals cloud the corneal stroma and progressively decrease visual acuity. Her sister Cathy was diagnosed soon after.

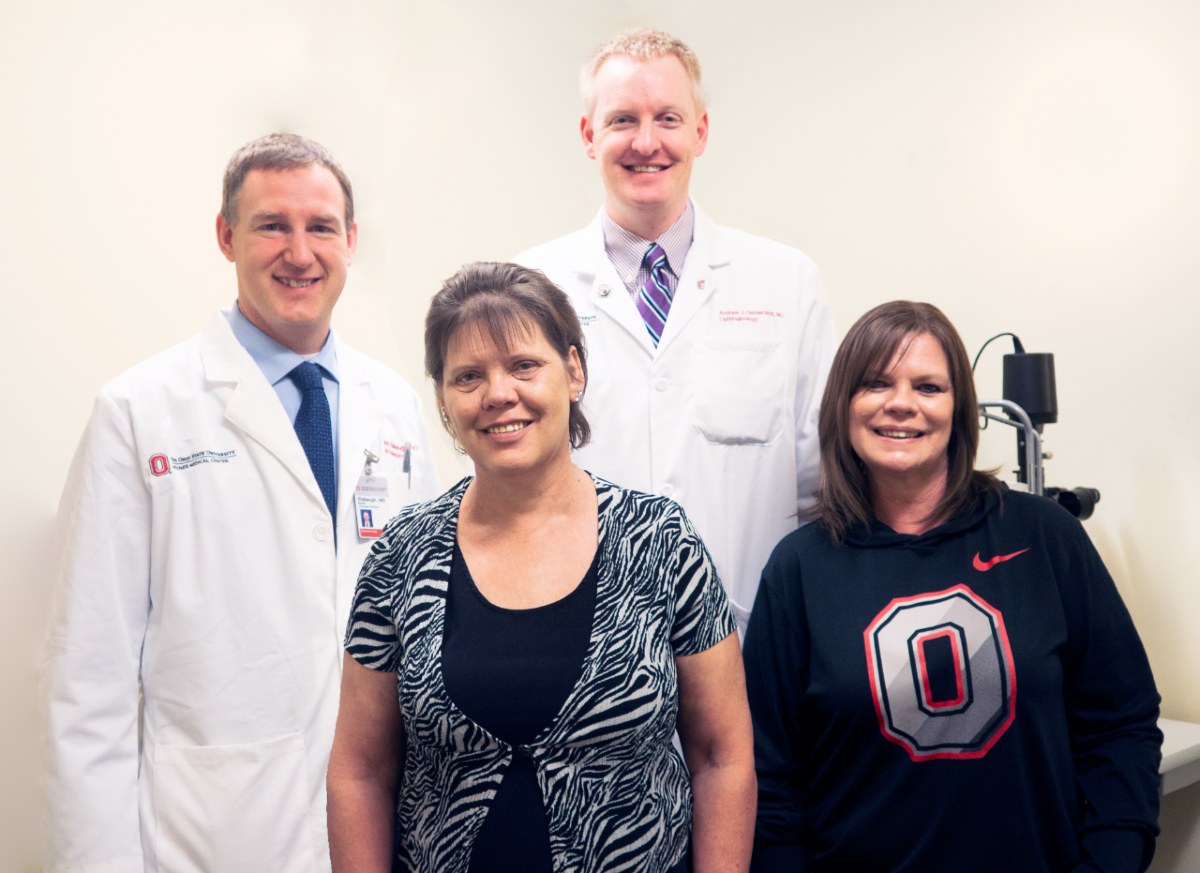

"There are probably plenty of doctors who have never seen this outside of a book," Dr. Andrew Hendershot says. Drs. Andrew Hendershot and Mark Slabaugh have worked together to perform the sisters' corneal transplants and cataract surgeries, respectively.

"I was scared of the cornea transplant," Laura, a cosmetologist, says. "But after a while I could no longer cut hair. Then I worked at a daycare, but it got to where I was falling constantly."

Cathy had to leave her job with Ohio parks and campgrounds after she became unable to read her computer screen.

"I was shocked when I looked at their eyes," Hendershot says. "I don't know how they saw."

In the past year, Cathy has had both corneal transplants and one cataract surgery. Laura has had one corneal transplant and one cataract surgery, and her second transplant was in March 2019. Both sisters will need their second cataract surgeries in the near future.

"My vision has improved tremendously," Cathy says. "Everybody here has been great. They make it a lot more comfortable when you have to come back and do it again."

Laura and Cathy are enjoying getting their lives back little by little as their vision improves post-surgery.

"I was able to drive three miles to take my granddaughter to the movies a couple weeks ago," Laura says. "It’s wonderful. It’s progress. I was grinning the whole time."

Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Trial

As a nurse, Leah Snow had patients involved in clinical trials, but she had never participated in one until Ohio State Ophthalmology approached her two years ago. Diagnosed with diabetes 26 years ago, Leah Snow’s only complication has been diabetic retinopathy in her right eye.

Diagnosed with diabetes 26 years ago, Leah Snow’s only complication has been diabetic retinopathy in her right eye.

“I’ve always wanted to take part in a clinical trial. I think it’s important to help," Leah Snow says.

Snow joined a clinical trial looking at an anti-VEGF medication already approved by the FDA. The goal of the research was to determine whether early administration of the drug can prevent progression of diabetic retinopathy.

"My main concern was will it hurt me at all. I was worried about whether it would harm my vision," Snow explains. But Barbara Mahalik, OD and Matthew Ohr, MD were able to alleviate her fears.

“Previously the drug hadn’t been approved for this specific indication,” explains Demarcus Williams, Clinical Research Coordinator at Ohio State. “We know that it works for macular edema, but not necessarily for this indication. So we have a good idea of the safety profile, however, we wanted to be able to prove it can help stop progression of this disease.”

This study was a two-year commitment to visit the clinic every month or every other month.

"To get good quality data, the patients have to be compliant," Williams says. "A missed visit is bad for the study, but more importantly it could be bad for the patient because it’s a missed opportunity for them to receive a treatment.

"I’m glad and thankful that Leah has been a star participant for us, and hopefully an advocate for new medical research and innovation."